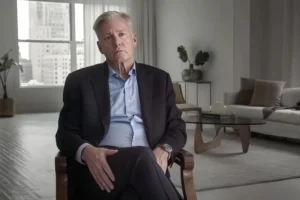

According To The variety It’s fitting that Michael Mann should be honored at the Lumière Festival in Lyon, since the director of “Ali,” “Heat” and “The Insider” began his filmmaking career in France. After graduating from the London Film School in 1967, Mann — who grew up in Chicago and switched course from a literature degree to filmmaking after seeing Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove” — was dead-set on directing dramatic features.

In the meantime, he found his way to Paris, documenting the student uprisings of 1968 as they happened. Mann adopted the protestors’ slogan, “Prenez une caméra et descendez dans la rue” (or “pick up a camera and take to the streets”), achieving what the American networks could not: He talked student leaders Daniel Cohn-Bendit, Alain Geismar and Alain Krivine into granting him interviews, edited into a segment called “Insurrection” and broadcast on NBC. Mann subsequently reshaped that footage into an abstract 8-minute short film (“Jaunpuri”), which screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1971.

Skip forward 10 years, and Mann was invited to world premiere his first theatrical movie, “Thief,” in competition at Cannes — quite an honor for a helmer so early in his career. “At that time, ‘The Jericho Mile,’ which is the Movie of the Week I did before ‘Thief,’ got theatrical distribution and was playing on the Champs-Élysées down the street from ‘Thief,’” Mann explains. “It was completely bizarre, particularly in those years when you couldn’t make a movie on an iPhone, after a decade or more of trying to get a film made, to have two of them [released] at the same time.”

Hosted by Cannes chief Thierry Frémaux, the Festival Lumière will screen all 12 of Mann’s theatrical features this week, before presenting him with the Lumière Award, following a master class on Friday, Oct. 17. The retrospective will also include his pilot for the Max series “Tokyo Vice” — the apotheosis of where Mann’s elevated aesthetic and commitment to authenticity intersect — and “The Jericho Mile,” a sports movie shot inside Folsom Prison featuring real inmates as extras.

“Human intelligence does not diminish when you confine a geographical space. If anything, the opposite happens,” says Mann, who was impressed by the prisoners’ interest in the craft. The director remembers one who asked him questions for half an hour, by the end of which he understood the principles of blocking and coverage.

The production arranged for several inmates to get Taft-Hartley permits, Mann explains, “which meant they got SAG minimum, on their commissary as opposed to making, you know, three cents an hour stamping license plates or something.” The one condition: There couldn’t be a race war between Folsom’s three gangs — the Black Guerrilla Family, the Bluebirds (a precursor to the white supremacist Aryan Brotherhood) and “La eMe,” Mexican Mafia — or the warden would pull the plug.

Three minutes into the movie, a member of the Black Brotherhood tells a journalist, “Everything’s for real. That’s our motto,” and while that isn’t exactly Mann’s mantra, the sentiment certainly aligns with his commitment to authenticity.

“The real is where I go. That’s where richness is for me: in real people, real circumstances, real trials and emotional tidal waves that happen to people,” Mann says. That applies whether he’s telling contemporary stories such as “The Jericho Mile” and “The Insider” or adapting a work of historical fiction, à la “The Last of the Mohicans.”

For that film — a pre-revolutionary American epic starring Daniel Day Lewis and Madeleine Stowe — Mann not only insisted on period-accurate set dressing and wardrobe, but also endeavored to channel the psychology of the time: What a young woman growing up in London’s updwardly mobile Portman Square neighborhood in 1757, would have thought, what kind of music she might have listened to (the answer: Handel) and so on.

“The Insider” was inspired by Mann’s friendship with Lowell Bergman, the “60 Minutes” producer (so ferociously embodied by Al Pacino) whose bombshell segment featuring a Big Tobacco whistle-blower spooked the upper ranks of CBS. Mann had been talking to Bergman about other projects when the network self-censored his interview with Jeffrey Wigand (played by Russell Crowe in “The Insider”), giving him personal insight into a big-business scandal.

“Whether I’m doing ‘Manhunter’ or ‘Heat 2’ or ‘The Insider,’ it’s the deep dive into real people … what it felt to be in their shoes and look through their eyes,” Mann says. “That’s what occupies me in the writing or the preparatory stage of it, and that’s where I find things that you cannot make up.”

In the case of “Manhunter,” Mann had been in contact with a convicted killer named Dennis Wayne Wallace, around whom he was trying to write an original screenplay, when he read Thomas Harris’ “Red Dragon.” The novel presented Mann with a plot in which to place his character, overwriting Harris’ ideas for “the Tooth Fairy” serial killer Francis Dollarhyde with details that interested Mann about Wallace, who had a fantasy relationship with a woman.

Wallace had told Mann that their love song (in the killer’s imagination, at least) was “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,” which is why the director used that music over the end credits. More important still was Dollarhyde’s dark humor, also drawn from Mann’s correspondence with someone who had truly been capable of such crimes. “Just because something’s real doesn’t mean you have to use it,” Mann clarifies. The director, who defined the ultra-stylized ’80s look of “Miami Vice” and brought a similarly heightened aesthetic to “Manhunter,” famously fills entire notebooks with the research and background material that go into preparing each project.

In “Thief,” he cast John Santucci, the thief on whom James Caan’s title character was based, as a corrupt cop. But his commitment to authenticity went one step further: “All the props in ‘Thief’ weren’t props. They were all his burglary tools,” Mann says. The thermal lance Caan uses to penetrate the safe was Santucci’s own burning bar. Other facets, like problems the characters had with wives and kids came from Mann’s interviewing Santucci and immersing himself in the man’s life. (Mann helped him get a SAG card and made him a series regular on his series “Crime Story” in the late ’80s.)

In studying both criminals and law enforcement officers over the years, Mann has repeatedly been fascinated by both the complexities and contradictions in their personalities. “I’ve interacted with some spectacular people in law enforcement who do things that are quite incredible and so complicated, they could be CEOs of major Fortune 500 companies, and nobody will know because they’re taking down Khun Sa, who was responsible for producing 65% of the world’s heroin.”

Mann invites interactions with anyone who could potentially be a character, adapting their life experience into details for his movies. Perhaps the most impactful example is Chicago police officer Chuck Adamson, whose experience informed aspects of Mann’s spectacular 1995 crime film “Heat.” Adamson once told Mann about how he’d sat down to coffee with Neil McCauley, a highline professional thief he later killed in a shootout — the basis of a dramatic tête-à-tête between Pacino and Robert De Niro in what has arguably become the director’s most iconic scene.

According to Mann, Adamson highly respected his quarry. “When he met him, he realized they had a kind of unique rapport. He really liked this guy, and at the same time, as he put it, he’d blow him out of his socks without thinking twice about it.” Mann appreciated that paradox and understood why McCauley might agree to meet with Adamson at the Belden Deli on Clark St. in Chicago. It was a way for both men to assess one another, since they understood — as the audience does in “Heat” — that they were on a collision course where only one would walk away alive.

I’m partial to the terse, reality-based psychology of “The Insider” and “Thief,” and the sleek, darker-than-noir elegance of “Collateral.” Still, “Heat” is Mann’s most elaborate film — in terms of both logistics and the sheer breadth of its ensemble — and the one many consider to be his masterpiece. In making it, Mann issued a challenge to himself: Could he construct a vast panoply of three-dimensional people (where even the most minor supporting characters have fully imagined lives) and program a meticulously precise structure that brings everything to that explosive collision?

No wonder it’s the only sequel he intends to make. The way Mann works, his characters are so fully realized that their lives seem to continue even when the cameras aren’t rolling. It’s only a matter of time before they do on “Heat 2” (which picks up right after the original with Val Kilmer’s character, Chris Shiherlis, a role Leonardo DiCaprio has reportedly been considering). The novel’s been published, and the notebook is being prepared. Because when Mann calls “action,” he means it.

+ There are no comments

Add yours